Newark's Kingsland Drum and Barrel

In the dwindling light of day, my first foray into an area earmarked for its industrial quietude was met with an unexpected hustle and bustle. Vehicles, in a steady stream, traversed back and forth along Station Road that, by all accounts, should have been deserted. It was a stark contrast to the preconceived desolation I had envisioned for such an industrial space. This initial encounter set the stage for what was to become a series of visits, each revealing more layers to the story of a place caught in the throes of transformation.

My second attempt to delve deeper into this evolving landscape was thwarted by construction crews who had laid siege to the roadway. Mere meters from where vehicles once freely entered, now stood a barrier of progress, digging into the earth, reshaping the roadway. It seemed as though every attempt to connect with this place was met with another obstacle, pushing my curiosity further.

By the time of my third visit, change had swept over the site with a vigor that left little of its former self. What once may have been a bustling hub of activity was now a cleared expanse, an empty canvas stripped of its past. The demolition had not discriminated; the interior had been pared down to its bones and a partial exterior landscape cleanup had occurred. Yet, as I traversed this barren landscape, my gaze was caught by the idle dance of transportation services—Uber, Lyft, and an array of private taxis—all in a patient wait outside the boundaries of the Newark Liberty International Airport monolith.

Guarding the entrance like silent sentinels of change were two pieces of heavy machinery, an excavator and a backhoe, their presence a testament to the transformation within. Inside, the land was flattened, a uniformity from front to back that spoke of the extensive work undertaken. All that remained was the earth beneath, punctuated by loose piping, the detritus of what once was. Toward the rear, a room that had succumbed to the pressures of demolition lay in a heap of rusted metal and debris. In another, a lone boiler sat, a ghost of its former utility, awaiting its final journey to the scrapyard.

The scene painted a poignant picture of industrial decline, a narrative of change, and the relentless march of progress. I had arrived too late to witness this corner of industry in its dying breaths, nestled awkwardly in a triangle of land surrounded by the sprawling expanse of airport parking businesses. Yet, adjacent to this scene of desolation, life buzzed with an indomitable spirit at the New Jersey Galvanizing and Tinning Works, Inc., continuing in industrial perseverance.

Nestled within the complex tapestry of the industrial evolution and environmental responsibility lies the sobering tale of the Bessemer Processing Company, Inc. (Bessemer), a narrative that unfolds against the backdrop of legal scrutiny and the undeniable impacts of industrial practices on human health. For over a quarter-century, Bessemer, a subsidiary of Kingsland Drum and Barrel, stood at the forefront of the petroleum and chemical manufacturing industries, specializing in the cleaning and reconditioning of fifty-five-gallon drums. These containers, marked by residues of the industries they served, required processes such as incineration, blasting, and recontouring to prepare them for reuse—a testament to the recycling efforts within these sectors.

However, beneath the surface of this recycling endeavor, a more troubling aspect of industrial activity lurked. Employees, including Walter James, found themselves enveloped in a hazardous work environment, where exposure to residues of petroleum products and various chemical substances was a daily occurrence. Among these substances were benzene and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), both recognized as human carcinogens. It was in these conditions that Walter James, alongside his colleagues, toiled day in and day out, unwittingly inhaling toxins that would later claim his life through stomach and liver cancer at the tragically young age of 55.

The case of James v. Bessemer Processing Co., Inc., which emerged from this tragedy, became a landmark moment in environmental law, particularly within the state of New Jersey. The ruling, which preserved joint and several liabilities under New Jersey’s Comparative Negligence Act for environmental tort actions, marked a significant turning point. It highlighted the complexities of apportioning negligence or fault in cases where the health impacts of industrial practices come to light. This legal precedent underscored the imperative for industries to reckon with their environmental and health-related responsibilities.

The narrative surrounding Kingsland and its subsidiary, Bessemer, unearths a tale of innovation and environmental strategy interwoven with the stark realities of industrial waste management. The companies’ ventures into the realms of medical and chemical waste disposal reveal a concerted effort to marry efficiency with environmental stewardship, albeit against the backdrop of legal challenges that paint a more complex picture of their operations.

At the heart of Kingsland's approach lies a series of patented technologies designed to revolutionize the reconditioning and disposal of metal-sealed barrels. These innovations, characterized by processes that allow for the flushing of barrels with liquid without fully opening them, demonstrate a keen awareness of the challenges inherent in waste management. The ability to recondition a standardized tight-head drum for reuse, whether in its original form or as a wide-neck drum, speaks to a commitment to reduce waste and extend the lifecycle of industrial containers.

Moreover, the specialized process for liquid waste disposal, particularly of the bio-hazardous variety, underscores a critical consideration for public health and safety. By preventing splashback and the aerosolization of dangerous pathogens, Kingsland's technology aimed to mitigate the risks associated with handling infectious diseases such as AIDS, hepatitis, MRSA, and tuberculosis. This innovation not only represents an advance in waste management technology but also a crucial step toward safeguarding workers and the wider community from the spread of infectious diseases.

The emphasis on reusing barrels, thereby avoiding the pitfalls of single-use canisters and the exorbitant costs associated with disposing of “red bag” waste, reveals a dual focus on economic and environmental sustainability. By extending the usable life of these containers, Kingsland and Bessemer sought to navigate the intricate balance between operational efficiency and the imperative to manage industrial and medical waste responsibly.

Yet, the legal entanglements involving Bessemer offer a reminder of the inherent challenges in ensuring worker safety and environmental protection within the industrial sector. These cases serve as a poignant reflection on the necessity of stringent regulations and robust safety protocols to protect those at the frontlines of hazardous waste management.

The mid-20th century marked a pivotal moment in the industrial landscape, particularly within the steel drum industry, an era characterized by innovation, resilience, and strategic adaptation. Amidst this transformative period, a press release from the 1950s sheds light on a practice that not only exemplified the ingenuity of the time but also played a critical role in sustaining the industry through economic and material challenges: the reconditioning, cleaning, and resale of used 55-gallon steel drums.

This practice, championed by Kingsland Drum & Barrel among other key players, emerged as a cornerstone strategy, enabling the drum industry to effectively recondition an impressive 35 million drums annually. This figure notably surpassed the production of new drums, which stood at 25 million yearly, highlighting the significant impact of reconditioning efforts on the industry's sustainability and resilience. At a time when steel prices and domestic production faced pressures toward price stabilization, such initiatives were not merely innovative; they were essential for survival.

The diversity of contents that these reconditioned drums housed—ranging from chemicals, foods, and lard to paint, alcohol, kerosene, and petroleum—underscores the versatility and indispensability of steel drums in various sectors. This adaptability, coupled with the economic efficiency of reusing drums, positioned companies like Kingsland Drum & Barrel as pivotal contributors to both the industry's sustainability and the broader efforts to manage resources more responsibly.

Among the esteemed ranks of the era's steel barrel and drum companies—such as Acme Steel Drum Co, American Cooperage Co, Rheem Manufacturing Company, J & L Steel Barrel Co, and others—Kingsland Drum & Barrel stood as a testament to the ingenuity and resilience of the industry. These companies collectively navigated the challenges of their time, leveraging reconditioning practices not only to withstand economic and material scarcities but also to contribute to a burgeoning ethos of sustainability that would, in many ways, prefigure contemporary environmental consciousness.

A Backyard Cemetery in an Industrial Zone

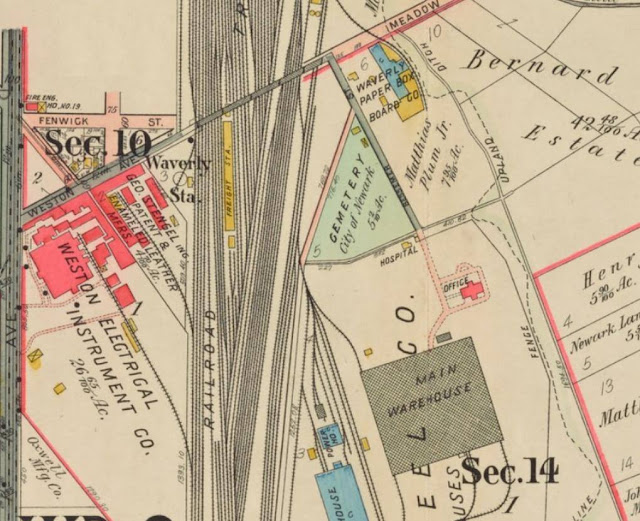

The discovery of Potter's Field, a forgotten piece of Newark's history, encapsulates a narrative that is as poignant as it is unsettling. Hidden in plain sight, this unassuming patch of green amidst the industrial sprawl near Newark Airport, once known by names such as Newark City Cemetery, Newark Municipal Graveyard, and Floral Rest, harbors a somber secret beneath its surface. Established around 1869, this burial ground was the final resting place for the city's poor, a three-and-a-half-acre testament to the societal norms and challenges of its time.

As the years marched on, the closure of the cemetery in the early 1950s marked the beginning of a profound transformation. The deceased, numbering over 18,000 souls, were left in situ, their existence obscured by the relentless march of progress and industrial development. The land that once offered a modicum of dignity in death was repurposed, contravening an 1880 law that mandates the removal and reburial of remains before such a change in land use can occur.

The lack of records, lost or destroyed, adds a layer of mystery and tragedy to Potter's Field, rendering it a silent witness to the forgotten chapters of Newark's history. The litigation entangling this city cemetery underscores a struggle between the past and the present, between respect for the deceased and the pressures of urban development. It is a stark reminder of the complexities inherent in reconciling historical reverence with contemporary needs. This revelation brings to light not just the physical obliteration of a cemetery but also the erasure of a significant part of the city's heritage. It serves as a poignant reflection on the values, decisions, and oversights that can lead to such a disquieting disregard for the past.

The narrative of the City Cemetery in Newark unfurls a complex tapestry that weaves together themes of memory, neglect, and the enduring quest for dignity. What was once a potter's field, a solemn space for the city's indigent, unknown, and unclaimed, has traversed a grim metamorphosis. The gradual repurposing of this sacred ground into a junkyard, and subsequently for industrial use, signifies a profound loss—not merely of a physical site but of the collective memory and respect owed to those at rest there. This transformation, shadowed by the advance of time and the exigencies of urban development, effectively obscured the cemetery's essence, relegating its inhabitants to the margins of history.

At the heart of this story of erasure and rediscovery is Elsie Lascurain, a woman whose life has been shaped by a relentless pursuit of closure and respect for her father, buried in the cemetery in 1921. Lascurain's journey, marked by decades of uncertainty and determination, casts a light on the deeply personal impact of the cemetery's neglect. Her legal battles against the city underscore a critical dialogue about the sanctity of burial sites, the responsibilities of stewardship, and the broader implications of forgetting those who once formed the fabric of the community.

Elsie Lascurain, at 84, embodies the struggle for remembrance and dignity. Her actions challenge the community and its leaders to confront the ethical dimensions of urban development and the importance of preserving historical and sacred sites. Her story, a poignant reminder of the individual and collective need for closure and respect, stands as a testament to the power of memory and the enduring human spirit in the face of neglect and oblivion.

The saga of Newark's City Cemetery unfolds as a profound reflection on the intersections of urban development, historical memory, and the dignity of the deceased, particularly those from less privileged backgrounds. This narrative is emblematic of broader societal shifts that have, at times, prioritized progress and economic considerations over the sanctity and preservation of final resting places. The transformation of the cemetery into an industrial site, without the relocation of the remains buried there, represents a stark breach of both legal and moral obligations, highlighting a grievous oversight in the stewardship of communal and historical spaces.

The ensuing legal and moral outcry against this oversight illuminates a growing societal insistence on honoring the deceased with dignity, irrespective of their socio-economic status. It calls into question the values that govern our approach to urban development and the legacy of those who preceded us. The challenges faced in efforts to restore the cemetery—stemming from its extensive repurposing and the lack of comprehensive burial records—underscore the complexities of reconciling past oversights with present-day aspirations for rectitude and respect.

The city's engagement in discussions to appropriately memorialize those buried at the site, including the consideration of archaeological excavations and the potential application of technology to locate graves, signals a pivotal step towards acknowledging and amending past transgressions. This approach not only seeks to honor the memory of the deceased but also serves as a crucial reevaluation of how societies maintain the dignity of all individuals posthumously.

At the heart of this narrative is the emotional journey of individuals like Elsie Lascurain, whose relentless pursuit of closure has galvanized a broader community awakening to the fate of the cemetery. Her story, and those akin to it, emphasize the profound human need for closure, respect, and the recognition of our shared history. It is a poignant reminder of the deep-seated connections that bind us to our ancestors and the places that hold their physical remains.

Current Progress

The current state of the site, now repurposed for long-term airport parking to accommodate the burgeoning flow of travelers from the nearby Newark Liberty Airport, reflects a continual evolution in urban land use, driven by the pressing demands of modern infrastructure and economic growth. This transformation, while serving the practical needs of the present, also layers new chapters over the historical narrative of the land, particularly the poignant story of the City Cemetery and the industrial legacy of Kingsland Drum & Barrel.

The addresses associated with Kingsland Drum & Barrel, 133-135 Haynes Avenue and 306, 308 Miller Street in Newark, NJ, stand as geographic markers to a complex past, intertwining the industrial heritage with the sobering history of the cemetery's forgotten souls. These locations, once bustling with the activities of drum and barrel reconditioning, now embody the silent witnesses to the inexorable march of progress and the shifting priorities of urban development.

For those seeking to delve deeper into the layered history of these sites, the “Empty Drum and Barrel” series offers a visual companion to the narrative, providing a tangible connection to the past through photographs. These images serve not merely as documentation but as a poignant reminder of the transience of place and purpose. They capture the essence of a time when these sites contributed to the industrial fabric of Newark, even as they quietly encompassed a chapter of the city's social history marked by neglect and eventual recognition.

The repurposing of the cemetery site for airport parking, while indicative of the city's adaptability to the needs of its inhabitants and visitors, also raises contemplative questions about the preservation of historical and communal memory in the face of relentless urbanization. It underscores the importance of acknowledging and integrating the many layers of a place's history as cities continue to grow and change.

Sources:

1. James v. Bessemer Processing Co., 155 N.J. 279 (1998).

2. Herszenhorn, D. (1998, October 19). (Speaking Out For the Indigent Dead; A Woman's Search for Her Father's Remains Is Forcing Newark to Restore a Potter's Field). NYTimes.

3. Westfeldt, A. (1998, December). (Loved Ones' Resting Places Discovered Under Garbage -- Families' Search Led To Discovery Of Lost New Jersey Cemetery). The Seattle Times.

4. The Official Guide for the Transportation of Hazardous Materials. (1989). United States: International Thomson Transport Press, Incorporated. pp.154.

5. Rudlin, D. A. (2007). Toxic Tort Litigation. United States: American Bar Association, Section of Environment, Energy, and Resources. pp.271.

6. Newark International Airport Ground Access Monorail, Northeast Corridor Connection Project, Essex County and Union County: Environmental Impact Statement. (1996). United States: (n.p.).

7. General Press Release. (1951). United States: Office of Price Stabilization.

8. Industrial Directory of New Jersey. (1949). United States: (n.p.). pp.728.

9. Official Gazette of the United States Patent Office. (1960). United States: U.S. Department of Commerce. pp. 33, 277.

Comments

Post a Comment