Former Crown Heights Consumers Park Brewery

In the annals of exploration, there are triumphs and then there are the tales that find their place in the losing column, etched as reminders of what might have been. Such is the story of my failed attempts to witness firsthand the historical significance of two cherished hometown landmarks in 2023. Among them stands the Empire State Dairy on Atlantic Avenue, a place steeped in the essence of bygone eras, where my endeavors ended in frustration and missed opportunity.

The second of my momentous failures unfolded within the walls of the Empire State Dairy. I hope others managed to breach its confines, while my own infiltration efforts fell short, leaving me estranged from its secrets. I lingered in my absence until news reached me, like an echo of finality, that the property was slated for redevelopment. It was a bitter realization, underscored by the fervent new buildings going up all over New York City like mushrooms. The first of my momentous failures occurred with the last old historical brewery, Consumer Park Brewery, located in Crown Heights Brooklyn. Others did it and my infiltration efforts failed so badly that I did not even return for so long before I was notified that the property was slated for demolition. I knew demolition was coming soon after that incident involving local children who inadvertently trapped a friend inside an old, forgotten safe. The intervention of the fire department in saving the minor’s life only underscored the urgency of the site's fate.

The whispers of those who had ventured within spoke of a place tinged with the scent of pungent spices—a vestige of its last incarnation as a spice factory. In addition, a view like no other across the bow of the old smokestack looking over to a new affordable housing development across the street only pained me even more. Here, amidst the remnants of industry, spices were ground and processed, destined for the shelves of retailers and the kitchens of restaurateurs.

My own attempts at entry were met with barriers, both physical and circumstantial. The padlocked doors of the smaller former subway station building remained beyond my reach, as did the inner fence line, fortified with a heavy metal sheet akin to the obstacle a mountaineer might face on a sheer cliff face.

Reflecting on my efforts, I realized the folly of my approach. Perhaps, with ingenuity, I could have found a way to widen the gap, to slip through unnoticed. But fate intervened, altering my plans with the capriciousness of a shifting work schedule. By the time I contemplated a third attempt, the news of the children's escapade had already reached me, signaling an end to my aspirations.

In the aftermath of the incident, I assumed the location would be secured, and guarded against further intrusion by the authorities or its current owner. Yet, I couldn't shake the feeling that perhaps, amidst the fervor of media attention, another opening had emerged, beckoning the curious and the intrepid.

You can see the partial demolition of the Interboro Brewing Company from 0.00 to 2.40 in the video above.

As fate would have it, just before the final curtain fell on the Consumer Park Brewery, an unexpected window of opportunity presented itself. The property lay open, inviting anyone bold enough to venture within its hallowed halls before the wrecking ball's imminent arrival. Yet, my cautious nature was at odds with the risk posed by the presence of wireless motion cameras strategically placed throughout the premises when I went back to see if it was still open to any and everybody.

The prospect of triggering these surveillance devices, potentially alerting unseen overseers, weighed heavily on my mind. It seemed that luck, that fickle companion of the urban explorer, favored me more readily in the distant locales of Connecticut, the upstate reaches of the Hudson Valley, and the western fringes of New Jersey. How perplexing it is to navigate the labyrinth of abandoned places, effortlessly breaching distant barriers while stumbling at the doorstep of my own hometown's secrets.

The missed opportunity at the Consumer Park Brewery remains a bitter pill to swallow—a regret that lingers like a persistent ache. The echoes of its vacancy along Franklin Avenue reverberate through time, a haunting reminder of what might have been. It's a sting that cuts deeper with each passing day, a testament to the elusive nature of exploration and the capricious hand of fate that guides our endeavors.

Check out a stunning collection of interior photos on Abandoned New York's Instagram page by clicking here.

|

| The faded "Consumers Park Brewery" is initialized in this stone facade. |

History

|

| Courtesy of NYC Tax Authority |

In the bustling landscape of early 20th-century Brooklyn, Charley Ebbets cast his vision for a ballpark that would become an emblem of the borough's identity. In 1908, as he scoured the neighborhoods near Prospect Park for the perfect location, his gaze fell upon an obscure area known as Crow Hill. Nestled between the districts of Flatbush and St. Marks, Crow Hill was little more than an undeveloped expanse, a forgotten ash dump dotted with industrial complexes.

Among these industrial enclaves stood the Flatbush Hygeia Ice Company at 984 Franklin Avenue, and nearby, the Consumers Park Brewery—a sprawling complex dedicated to the production of lager beer, a beverage synonymous with Brooklyn's spirit. For Ebbets, the proximity to both ice and beer seemed serendipitous, though the decision to build Ebbets Field there was more pragmatic than poetic. Land availability, transportation accessibility, and financial considerations weighed heavily in the selection process, yet there's a certain Brooklyn charm in the notion that a ballpark would rise mere blocks from a brewery.

When Ebbets Field welcomed its first fans in 1913, home to the iconic Brooklyn Dodgers and later, the legendary Jackie Robinson, the Consumers Park Brewery had already faded into history. The brewery was the brainchild of a visionary group of over two hundred hoteliers and saloon keepers who sought to wrest control of their product from the grips of larger breweries. Led by Herman Raub, a German immigrant, and seasoned hotelier, the brewery's inception marked a bold stand against the monopoly of beer prices and quality.

Herman Raub himself embodied the immigrant success story. Arriving in New York at just fifteen years old, he quickly rose through the ranks of the hospitality industry. By twenty-three, he owned the Central Railroad Hotel, an esteemed establishment opposite Grand Central Station. His entrepreneurial spirit and leadership qualities made him a natural choice as the first president of Consumers Park Brewery—a position he assumed at the young age of thirty.

In the narrative of Brooklyn's history, the tale of Ebbets Field and the Consumers Park Brewery intertwine, emblematic of the borough's vibrant spirit, entrepreneurial drive, and the enduring legacy of its immigrant communities.

With grandeur befitting its ambition, the Consumers Park Brewery complex opened its doors on January 6, 1900, amidst a flurry of celebration and festivity. The event drew over 500 stockholders and their friends, eager to witness the brewery's debut.

|

| Beer barrels were a part of the exterior architectural features of the building and its past use. |

The highlight of the day was the ceremonial tapping of the first keg. Herman Raub, the brewery's president, and F. Sievers, the brewmaster, performed the honors with a silver spigot and mallet. The first drops of beer were collected in a rose-bedecked, hand-painted stein. Adding a poetic touch to the ceremony, A.J. Westermayr recited a poem dedicated to the brewery.

After the keg tapping, attendees toured the brewery's impressive facilities, including the state-of-the-art storage house, the meticulously designed malt house, and the robust stables, each showcasing the brewery's commitment to excellence.

The evening concluded with a lavish banquet for 600 guests in the cooper shop, which had been transformed into a grand dining hall. The menu was elaborate, reflecting the brewery's dedication to quality. Toasts were made by key individuals, including Herman Raub, Charles F. Terney, Arthur J. Westermayr, Chau Paul Urff, Frank Raub, and Ferdinand Sievers, each celebrating the brewery's success and vision. The brewery was set to open to the public the following day, with the first commercial keg delivery scheduled for Saturday.

The brewery boasted more than just beer production—it was a multifaceted destination, complete with the Brick Hill Hotel, a culinary haven where guests could indulge in fine dining. The hotel also housed a restaurant, offering a taste of culinary delights alongside the refreshing brews produced on-site. Adding to the allure, a sprawling beer garden and concert facilities provided entertainment and relaxation for visitors.

|

| Consumers Park Station - Courtesy of NYC Tax Authority Records |

By 1902, the brewery's influence had grown, evidenced by the inauguration of the Consumers Park Station, a new stop on the Brighton Beach Line. This railway station, established by the old Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company, served as a convenient gateway to the brewery complex. Passengers disembarking at Consumers Park Station were greeted with pathways and bridges leading through the bustling brewery grounds, or out to Washington Street, offering a leisurely stroll to the nearby Prospect Park.

In an era when entertainment came at a modest price, the brewery complex offered a haven of enjoyment. For a cost that scarcely equaled the tip of a modern waiter, guests could partake in dining, dancing, and, of course, the finest brews Brooklyn had to offer. A German-style meal at the establishment cost only 50 cents. A far cry from today's restaurant prices anywhere in Brooklyn.

While the Botanic Gardens had yet to grace the landscape, and the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Science (now the Brooklyn Museum) was still under construction, Consumers Park Brewery stood as a beacon of leisure and hospitality, drawing visitors from far and wide to experience its unique blend of culture, cuisine, and craftsmanship.

In the vibrant landscape of Brooklyn's brewing scene, lager beer reigned supreme, capturing the hearts and palates of New Yorkers across the borough. Bushwick and Williamsburg were already home to a multitude of breweries, and new ventures were sprouting up in other neighborhoods, including Bedford-Stuyvesant and Crown Heights.

Among these brewing giants stood the old Consumers Park complex, a testament to Brooklyn's enduring love affair with lager. In the nearby Crown Heights neighborhood, another notable brewery, the Nassau Brewery, held court on Franklin Avenue, Bergen, and Dean Streets. Coincidentally, both breweries sat along the historic Brighton Line, weaving a thread of brewing heritage through the fabric of the borough.

Unlike English ales and stouts, which rely on top-fermenting yeast and warmer temperatures for fermentation, lager beers are crafted using bottom-fermenting yeast in cooler conditions, a process that typically takes six to ten days. This distinction in the fermentation process meant that ice was a crucial component of lager brewing.

To ensure a steady supply of ice for brewing, the Flatbush Hygeia Ice Company was established in 1898 by a group of Bushwick brewers. Situated adjacent to the Consumers Park Brewery, Hygeia played a vital role in the brewing process, controlling the production and collection of ice for the breweries in the area. In the competitive world of commodities, ice was no exception, and having Hygeia nearby provided Consumers Park with a reliable source of this essential ingredient.

The Hygeia factory once occupied the entire lot adjacent to the old Consumers' buildings on Franklin Avenue, a silent witness to the bustling activity of Brooklyn's brewing past. Together, these businesses formed the beating heart of Brooklyn's brewing culture, where tradition, craftsmanship, and competition converged to create the distinctive flavors that defined an era.

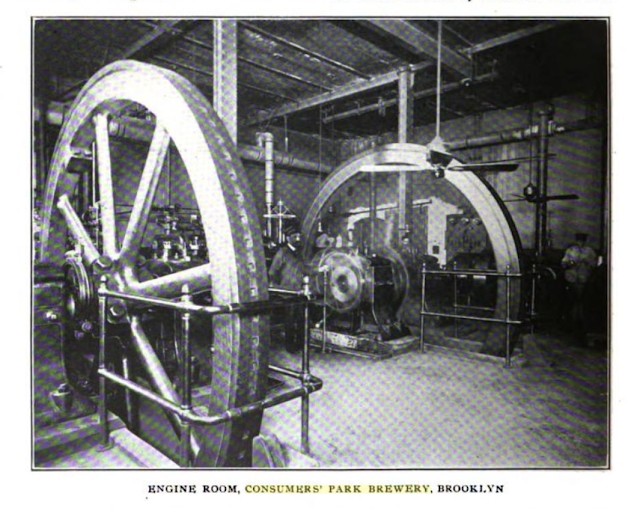

Consumers Park Brewery stood as a pioneer of progress in more ways than one. Not content to simply brew beer, it embraced innovation, becoming the first all-electric brewery in the United States. This technological leap not only revolutionized the brewing process but also illuminated the path for development in the surrounding neighborhood.

With electricity coursing through its veins, the brewery became a beacon of modernity, attracting attention and investment to the burgeoning community. Homes near the brewery were among the first in Brooklyn to benefit from this newfangled technology, ushering in an era of rapid development. Crown Heights South, the area nestled between Eastern Parkway and Empire Boulevard, experienced a surge of growth, with rowhouses, single-family homes, and apartment buildings sprouting up as if overnight.

At the helm of this bold venture was Herman Raub—a man whose resume bespoke of ambition and tenacity. The Consumers Park Brewery was his brainchild, a testament to his vision and determination. In 1901, with the brewery still in its infancy, Raub proudly announced in the Brooklyn Eagle that over 71,953 barrels of beer had been sold within its first year of operation. Such remarkable success allowed the company to pay a dividend of 7 percent from its inaugural year's earnings—an impressive feat for a brewery less than two years old.

But Raub's influence extended beyond the brewery's walls. Actively engaged in the German community, he sponsored numerous social activities centered around food, dance, and, of course, beer. Whether at Consumers Park Brewery or other venues in Bushwick, Raub knew how to throw a memorable party, earning him a reputation as a beloved figure in town.

His name echoed through the streets of Brooklyn, synonymous with hospitality, innovation, and the spirit of celebration. In the annals of Brooklyn's history, Herman Raub and Consumers Park Brewery stand as icons of progress, embodying the spirit of a bygone era defined by bold endeavors and the pursuit of excellence.

In 1907, Herman Raub's tenure at Consumers Park Brewery came to an abrupt and contentious end. Losing the confidence of his board, Raub found himself embroiled in an ugly power struggle that ultimately led to his ousting from the company. Returning to his hotel business, Raub's departure marked a disappointing chapter in his illustrious career.

Despite his earlier triumphs, Raub's flame burned fiercely and briefly. Tragically, he passed away at the young age of forty-six in 1915, leaving behind a legacy of ambition and achievement.

In 1913, two years before Raub's untimely death, Consumers Park Brewery underwent a significant transformation. It merged with the New York and Brooklyn Brewing Company to form the Interboro Brewing Company. The iconic smokestack, bearing the name "Interboro" etched into its brick facade, still looms over the complex—a silent sentinel of Brooklyn's brewing heritage.

The Interboro Brewing Company continued to thrive until the 1920s when the specter of Prohibition cast its shadow over the industry. Like many of its counterparts, Interboro fell victim to the nationwide ban on alcohol, closing its doors as the era of Prohibition took hold. Today, the faded remnants of Interboro's advertising can still be glimpsed on the weathered walls of the building, a poignant reminder of a bygone era.

|

| The "Interboro Brew" naming was lettered out on the other side of the smokestack. I did not get that shot sadly. |

The site of Consumers Park Brewery, and later Interboro Brewing Company, would bear witness to further tragedy. In 1918, the nearby section of the old Brighton Beach Line became infamous for the Malbone Street Disaster—a horrific train wreck that claimed the lives of over 100 people. This tragedy forever altered the landscape of Malbone Street, prompting its name change as a solemn memorial to those who perished.

November 1, 1918, stands as a somber day in Brooklyn's history, marked by tragedy near the site of the Malbone Street subway wreck. A strike by BRT subway motormen prompted dispatchers and supervisors, including the inexperienced Antonio Luciano, to operate trains. Assigned to the Brighton Line for the first time, Luciano faced a fateful journey as he navigated an S-shaped curve at speeds far exceeding the 6 MPH limit—reportedly around 50 MPH.

The catastrophic result was the derailment and destruction of the second and third cars, claiming the lives of approximately 100 passengers. Amidst the wreckage, Antonio Luciano miraculously survived, though haunted by the events that unfolded.

In the aftermath of the disaster, the name of Malbone Street was forever changed to Empire Boulevard, a solemn acknowledgment of the lives lost and the need to move forward. Only a small portion of the street retained its original name at the intersection of Montgomery Street and Nostrand Avenue, serving as a poignant reminder of the tragedy that occurred.

The line where the disaster took place eventually became part of the BMT line and later the Franklin Avenue Shuttle, though its use dwindled over time. The Consumers Park station was shuttered, its platform removed, leaving behind only traces of its existence.

From the vantage point of the bridge, one can still discern where the old station once stood, attached to the most remarkable and aesthetically pleasing building in the complex—a fanciful Gothic-style factory building poised at the edge of the tracks. It serves as a silent sentinel, bearing witness to the passage of time and the tragedies that have shaped the landscape of Brooklyn's history.

|

| During demolition, workmen walk on top of an ongoing portion of the building. |

After the closure of the brewery, the sprawling complex found new life as the Daisy Mattress Factory, with a faded advertisement for the mattresses still visible atop the old brewery building. In 1955, the site changed hands once again, this time becoming home to the Morris J. Golombeck Spice Company, a family business that had been operating since 1931.

For decades, the Golombeck Spice Company thrived in this expansive space, selling wholesale and bulk spices of all varieties. From peppers to basil, cardamom to cloves, the warehouse stored tons of aromatic treasures, creating a sensory overload akin to stepping into a bustling Middle Eastern spice market of old. Not only did they store spices for sale, but they also undertook the manufacturing, blending, and grinding of spices on-site.

Over the years, locals walking by the factory were greeted by a symphony of spice aromas, with nutmeg often dominating the olfactory landscape. The Golombeck Spice Company remained a fixture in the building until the 2010s when it was absorbed into the Schiff Food Products spice company.

Following the buyout, the building stood vacant, a silent witness to the changing landscape of Brooklyn. Today, it stands as the last vestige of the three companies that once graced Franklin Avenue. However, its days are numbered, as demolition has been completed, claiming even the old Consumer Park station.

In its place, luxury high-rises are slated to rise, signaling yet another chapter in Brooklyn's ongoing battle with development and preservation. Similar towers have faced local backlash, as they threaten to encroach upon the Brooklyn Botanical Gardens, restricting sunlight and altering the neighborhood's character.

The demolition of historic buildings to make way for luxury developments continues to be a contentious issue in Brooklyn, and this brewery-turned-spice factory is no exception. As the wrecking ball swings, it serves as a reminder of the delicate balance between progress and preservation, and the enduring legacy of Brooklyn's industrial past.

Today, the old Consumers site bears little resemblance to its bustling past. Most of the buildings have vanished, leaving only the foundation of the brewery's former glory. In the past, or a fever dream, the main brewery building, once a hive of beer production, also became the heart of the Golombeck Spice Company operation. As one peers down the enclosed entryway to the factory entrance, a classic 19th-century loading dock comes into view, ladened with bags of spices rather than barrels of beer.

Gone is the towering smokestack that once dominated the center of the complex, a silent sentinel of Brooklyn's brewing heritage. The most striking building, with its Gothic Revival style, the Consumer Park Station, adorned with fanciful gables and dormers, has been dismantled, its loose red bricks carted away. Yet, this building captured the attention of passersby, a testament to its architectural grandeur.

Surrounded by the growing gentrifying neighborhood of Crown Heights, the old Consumers site has been obliterated from view. First, Ebbets Field stood just a block away, a beacon of sporting excitement, before making way for the apartment buildings of the Ebbets Field Houses. In its wake, other apartment buildings and a whole neighborhood have flourished, concealing the brewery for a time but from all but the most curious seekers.

As one of the last remaining brewery complexes in the city, the old Consumers site holds a special place in Brooklyn's history—a relic of a bygone era when beer flowed freely and industry thrived. Though its physical presence may fade with time, its legacy endures, a reminder of the resilience and evolution of urban landscapes.

Sources:

1. (1901, January 2). The Standard Union, p. 7

2. Devlin, S. (2017, July 10). (Beers Gone By: The Life, Death and Rebirth of 5 Brooklyn Breweries). Brownstoner.

3. Consumers Park Brewery Co. HistoricBeerBottlesnNYC.

4. (2014, October 30). (Consumers Park Brewery). eatingintranslation.

5. (2023, May 12). (Consumers Park Brewing Co., Brooklyn, N.Y.). Bay Bottles.

6. Goba, K. (2019, February 25). (Developers Propose Massive 960 Franklin Avenue Project). Bklyner.

7. (2019, September 14). (Crown Heights to Prospect Park). Forgotten NY.

8. Rosenburg, Z. (2019, February 18). (Crown Heights megaproject could bring 800 affordable apartments to Brooklyn). Curbed NY.

9. Plitt, A. (2017, October 31). (Former Crown Heights brewery could give way to 30-story towers). Curbed NY.

10. Hubert, C. (2021, February 26). (Locals push back against updated proposal for Crown Heights Spice Factory site). Brooklyn Paper.

11. 960 Frankin, 960franklinnyc.

12. Spellen, S. (2012, July 5) (Walkabout: Crown Heights’ Consumer Park). Brownstoner.

13. The Brooklyn Citizen. (1902, May 11). (Consumers Park Brewery Ready to Entertain Guests). Page 11.

14. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. (1953, May 17). Page 33.

15. The Standard Union. (1901, March 29). Big Bock Beer Festival. Page 7.

16. The Standard Union. (1900, January 4). New Brewery Opened. Page 5.

17. Weiss, D. A. (2017). The Brooklyn Trivia Book. United Kingdom: Trafford Publishing.

18. Onofri, A. (2017). Walking Brooklyn: 30 Walking Tours Exploring Historical Legacies, Neighborhood Culture, Side Streets, and Waterways. United States: Wilderness Press.

19. The International Steam Engineer. (1906). United States: International Union of Steam and Operating Engineers. Page 594-596.

Comments

Post a Comment